School safeguarding, within the context of international schools, encompasses a broad range of practices and concerns aimed at protecting children’s health, well-being, and human rights. Initially, the focus of safeguarding in these settings was primarily on preventing sexual abuse by educators through measures like safer recruitment and criminal background checks. However, this understanding has significantly broadened over time to include other forms of harm and comprehensive well-being. The evolving scope of safeguarding in international schools now covers:

• Harm between children (peer-on-peer abuse)

• Affluent neglect

• Online harm such as bullying, sexual harassment and exploitation

• Identity-based harm such as racism, Islamaphobia or homophobia

• Student mental health and well-being, including issues like suicidal ideation and self-harm

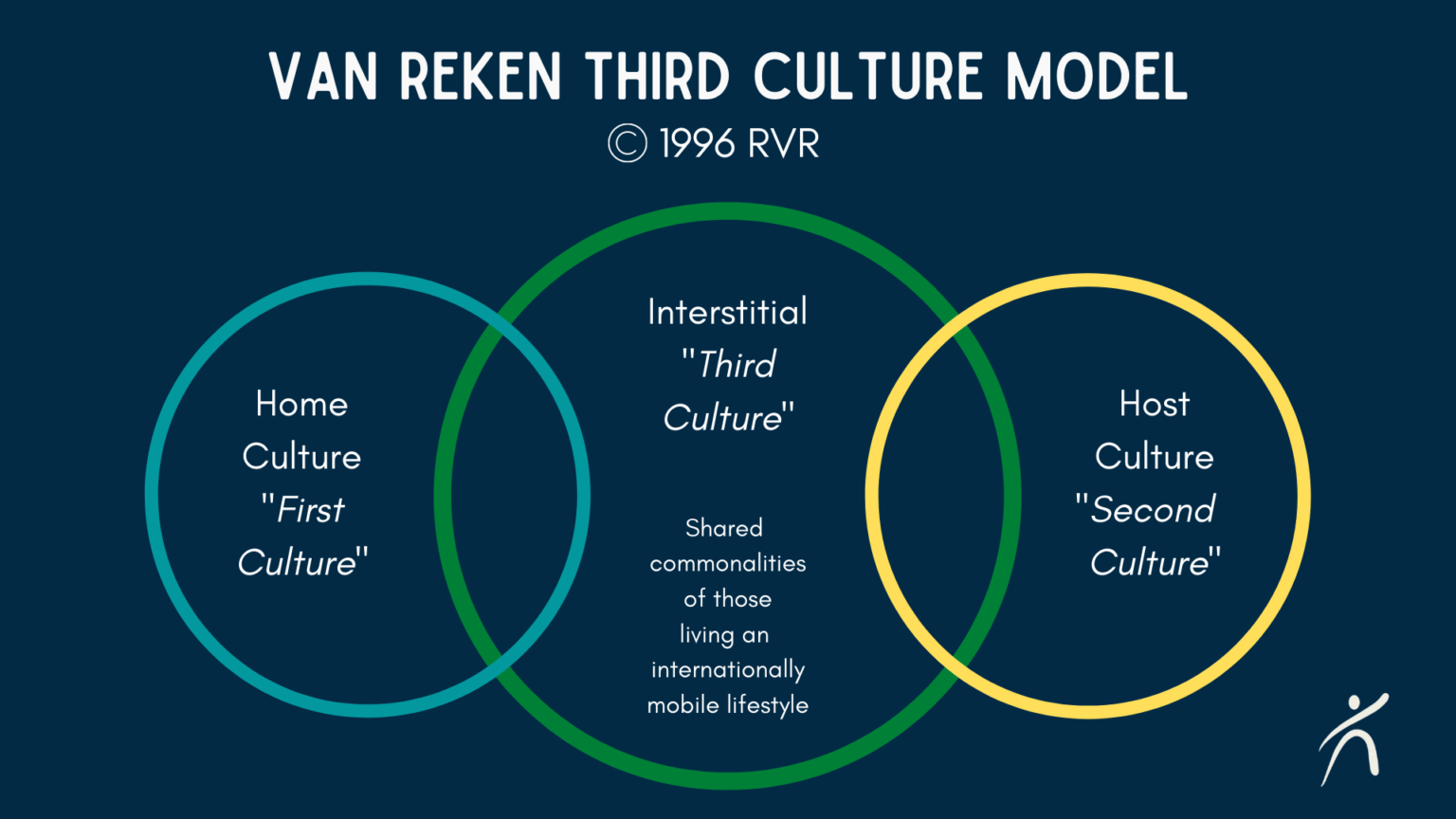

• The impact of transition on well-being for internationally mobile students (Third Culture Kids or TCKs)

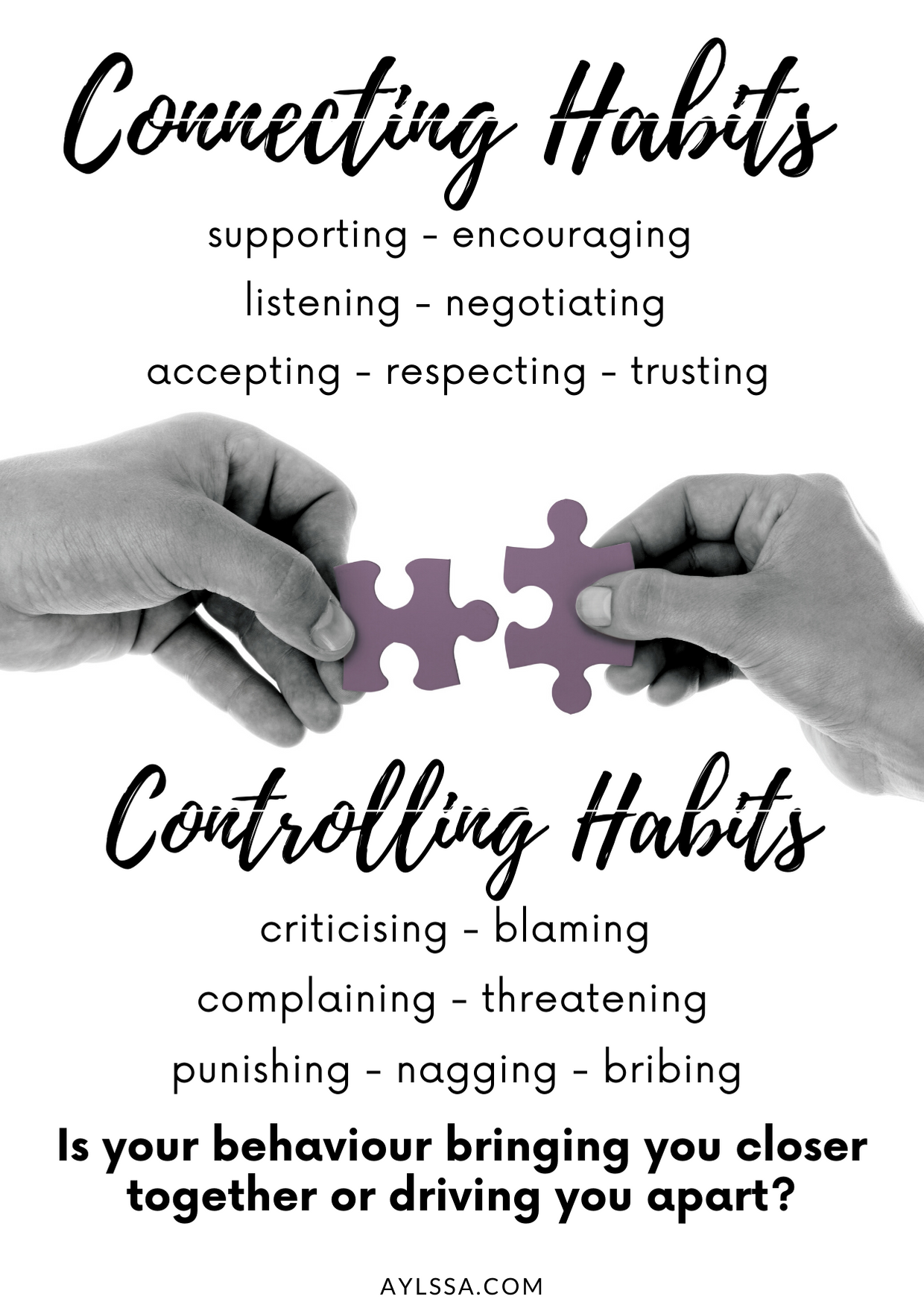

•Fostering a sense of belonging and respectful, trusting relationships within the school community.

This broadened approach also recognizes the interlinkage with data protection and the need for whole-school strategies.

Challenges to Safeguarding in International Schools

International schools, despite often having significant resources, face unique and complex challenges in implementing effective safeguarding practices due to their diverse populations, mobile nature, and varied legal and cultural contexts.

Affluent Neglect:

This is a particularly challenging area, as affluent families are often perceived as “low risk”. However, children in these families can experience severe emotional neglect due to parental isolation, excessive pressures for achievement, and a focus on material provision over emotional needs. This neglect is often masked because physical needs are met. Independent boarding schools may struggle to identify these children as being “in need or at risk of significant harm, and designated safeguarding leads (DSLs) can be reluctant to raise concerns due to parents’ transactional arrangements with schools or their power and influence.

Peer-on-Peer Abuse:

There is limited academic research specifically on peer-on-peer abuse in international schools. Forms of harm include cliques, gossip, anti-snitching cultures, sexual harassment and assault, peer pressure, social exclusion, physical assault, and specific issues related to nationality hierarchies or geopolitical tensions. Addressing harm that occurs outside school premises, including online, is complex and unclear, with many schools lacking adequate policies or legal clarity on their intervention scope.

Cultural and Legal Barriers:

International schools operate across 159 countries with diverse cultural and legal contexts. Conflicting cultural norms around discipline (e.g., physical punishment), care-giving, sexuality, and reporting can cause confusion and undermine safeguarding efforts. Some laws criminalize behaviors like certain sexualities or mental health issues, increasing student vulnerability and schools’ reluctance to report.

Relationship with External Agencies:

Many international schools are isolated from their surrounding communities and local agencies, operating in a “grey legal and political area. There can be a lack of trust and cooperation with local law enforcement and child protection services, with some agencies perceived as ineffective, corrupt, or even potentially causing greater harm to the child if abuse is reported. This leads schools to manage issues internally or rely on embassies and NGOs instead of statutory services.

Parental Power and Influence:

Affluent and influential parents can exert considerable pressure on international schools, sometimes undermining investigations or demanding specific outcomes to protect their family’s reputation or status.

Transitions and Staff Turnover:

Frequent student mobility (TCKs) and high staff turnover can hinder the development of trusting relationships and effective information sharing, making it difficult to identify patterns of harm or transfer safeguarding concerns between schools.

Application of Western Models:

Many international schools apply child protection models that originate from Western countries (e.g., UK, US, Australia), which may not align with local cultural and legal contexts. This can lead to resistance from local parents and professionals, perceived as a “western imposition,” and may be less effective than culturally contextualized approaches.

Safeguarding Practices and Enablers

Despite these challenges, international schools employ various strategies and leverage specific roles to support safeguarding:

Role of Counsellors and DSLs:

School counselors are identified as key personnel for supporting students’ unique developmental and mental health needs, particularly TCKs. They are often seen as trusted adults and play a critical role in developing and delivering student education and transition support. However, clarity on the division of roles and collaboration between counselors and Designated Safeguarding Leads (DSLs) is important. DSLs are responsible for overseeing safeguarding, and strong leadership by principals and DSLs who prioritize safeguarding and empower staff is a powerful positive force.

Policies and Procedures:

Clear, written safeguarding policies and procedures are crucial. Centralized, digital record-keeping systems for safeguarding concerns help identify patterns and intervene early.

Student Voice and Education:

Involving students in co-constructing safeguarding strategies and providing education on topics like consent, healthy relationships, and online safety is vital. However, time and resource constraints can be barriers to effective curriculum delivery.

Team Approach:

A team approach to managing safeguarding concerns, involving multiple professionals, is valued as it shares the burden and strengthens practices. Regular multi-disciplinary meetings help discuss student concerns.

Networks and External Support:

Engaging with local networks of international schools, international accrediting bodies (like CIS), training providers, and other external organizations provides valuable guidance, support, and external validation. Building relationships with individuals in local law enforcement, child protection agencies, and community-based NGOs can also strengthen practices

Culturally Responsive Strategies:

Developing strategies to work in partnership with families on sensitive issues, such as physical discipline in the home, by aligning with school values and educating parents can be effective15221. The need for cultural matching and contextualization of safeguarding approaches is particularly strong when Western professionals serve non-Western communities19….

In conclusion, school safeguarding in international schools is a complex and evolving field, moving beyond traditional concerns to encompass a holistic view of child well-being. While progress has been made in establishing foundational practices, significant challenges persist, particularly related to the unique cultural, legal, and social dynamics of globally mobile communities and the influence of affluent families. Addressing these challenges requires culturally informed, collaborative, and adaptable approaches, along with continued research to understand the diverse experiences of students and optimize safeguarding interventions.